Egypt in England Newsletter

2014

January

Happy New Year

A belated Happy New Year to everyone, and once again a newsletter makes it out in its target month by the skin of its teeth. One of my new year resolutions should be to avoid this happening.

Egypt on the beach

I don't know what the weather is like where you are, but here in Egyptian London it is cold, wet, and windy. Not what you think of when you think of Egypt. So I thought it might brighten things up a bit if I included a couple of photos of some unusual Egyptiana that I came across in Brighton in August 2005. I should perhaps point out, for anyone who doesn't know that city, that it doesn't have a naturally sandy beach. In fact, the 'beach' is made up of flint pebbles worn smooth by the sea, ranging from fist sized or bigger down to something that you could still only count as sand if you were being very generous about the grain size. Hobbling down to the usually cold and wind lashed sea across what feels like piles of stone tennis balls is part of the quintessentially British experience that is a day at the seaside in Brighton.

So how did they make these Egyptian themed sculptures? They used several tons of imported Belgian sand. Apparently it has to be the right sort of sand for sculpting, with sharp edged grains. It comes from rivers, because beach sand has been worn smooth by the action of the sea. In many ways, this was the ultimate in Egyptian ephemera, not only temporary, but especially vulnerable to any change in the weather. Does anyone know of anything similar anywhere else?

At last, you can Look Inside

After a long-drawn-out process of obtaining agreement from rights holders to the illustrations in Egypt in England (see previous newsletters), the Look Inside feature now works on Amazon. All I can say is, next time, I'll know to get agreement before writing the book.

Twilight of the Odeon

I read recently that the Odeon in Leicester Square is to be demolished and replaced by a hotel and spa. A token two screen cinema will be included as well, but it isn't quite the same. So what does this have to do with Ancient Egypt, I hear you ask? Well, No. 28 Leicester Square, the site of which is currently occupied by the Odeon, was not only the location of the first Hunterian Museum, which is now in the Royal College of Surgeons, but in 1825 housed the exhibition of reliefs from the tomb of Sety I originally shown by Giovanni Belzoni in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, and revived after his death by his wife Sarah. Sadly, it was not a financial success, and although influential friends and well-wishers organised a subscription to raise money for her to live on, she had to leave England for Belgium, where she lived for a number of years before moving again to the Channel Islands, where she died. As Michael Caine is alleged to have said, not many people know that. (For the movie trivia geeks out there, and you know who you are, whose impersonation of Caine was the actual source of the quotation?)

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

February

Last Call for the EES Seminar

This will be a fairly short newsletter this month, as I am preparing (as some recipients will also be!) for the Egypt in England seminar at the Egypt Exploration Society's offices in London on Saturday 22nd March.

Feedback from the EES indicates that take up has been "very popular", so if you are thinking of going I'd be quick about getting a ticket.

http://www.ees.ac.uk/events/index/247.html

Our American Cousins?

I don't know if any of you are members of the American Research Centre in Egypt (ARCE), but I am in the process of writing an article for their newsletter on Egyptian style architecture in England and America. In the course of research for this I came across an image of the Landon mausoleum in Kensico Cemetery, New York which immediately raised questions. Take a look at the images below and you will see what I mean.

On the left is the Illingworth mausoleum in Undercliffe Cemetery, in England, on the right the Landon mausoleum in Kensico Cemetery in the USA. Both clearly Egyptian style, although not identical, but both sporting sphinxes in a very distinctive Middle Kingdom style. Like the mausoleums, not identical, but similar enough to suggest that they share a connection. The Illingworth mausoleum was built for the Bradford textile magnate Alfred Illingworth in 1907. The Landon mausoleum must postdate the foundation of Kensico Cemetery in 1889, and was probably built in the early years of the 20th century, but at the time of writing I have not been able to establish the precise date of its construction, or find biographical information on its occupant. To the best of my knowledge, these are the only mausoleums with such highly unusual sphinxes guarding them, and it is almost impossible not to assume that there must be some connection. But which came first, and how did the designer of the other come to know about a monument on the other side of the Atlantic? If you know, please tell me. Otherwise, I will keep looking for answers myself.

(Those of you familiar with the espionage novels of John le Carré will remember that his British spies refer to their transatlantic counterparts as "our American cousins". What you may not be aware of is that this is probably a reference to the 1853 farce 'Our American Cousin', by the English playwright Tom Taylor. Which just happened to be playing at Ford's Theatre on the night of April 14th 1865, when one Abraham Lincoln was in the audience. And the rest, as they say, is history.)

A couple that I missed...

My only excuse is that even the magisterial James Stevens Curl seems to have missed these as well, in his 'Egyptomania', but I do wish that I had found them in time for inclusion in Egypt in England.

The first is the 15 foot high Douce mausoleum, from 1748, in the churchyard of St Andrew's at Nether Wallop in Hampshire. Interesting not only as another example of what might be called 'Proto-Egyptian' architecture, as it predates the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, and as another pyramidal mausoleum, but also for the carved decoration on its summit. More about why this, and some obelisks as well, have flames at their summits, in another newsletter.

The second is the Burrard Neale obelisk, or Walhampton Monument, at Lymington in Hampshire, commemorating the British admiral Sir Harry Burrard-Neale (1765-1840) and built by public subscription in 1842. It seems the winning design was by the little-known George Draper of Chichester, but another design was submitted by the better-known William Railton, of Nelson's Column fame. Superficially similar to other obelisk monuments around the country, closer inspection reveals that it has Egyptianising details, including a cavetto cornice, a rather stylised winged solar disk, and torus mouldings around the bronze plaques, which can be seen in the photo below. (Copyright Jim Champion.) Initial research has not turned up any obvious Egyptian connection for Sir Harry, but suggests that Railton's proposed design was inspired by the obelisk of Hatshepsut at Karnak, which he saw whilst visiting Egypt.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb,

Chris

March

Connecting People and Place

Until recently, only two of the iconic Blue Plaques in London commemorated Egyptologists. The now-defunct London County Council put up the first, to commemorate Sir Flinders Petrie, in 1954, and then English Heritage affixed the second to one of Howard Carter's residences. Now, I may be biased, but Egyptologists as a group seemed to me to be seriously under-represented. There isn't, as far as I am aware, a list of Plaques by category, but a quick search of the English Heritage database showed that there were, at the time of writing, 48 for Artists, 40 for Authors, 36 for Architects, and (surprise, surprise) 76 for Politicians.

Initially, I applied for one for Sir Alan Gardiner, the great philologist, who worked with Howard Carter on the texts in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Gardiner's greatest work, however, was probably his 'Egyptian Grammar', which was the text which started generations of Egyptologists, professional and amateur, on their study of hieroglyphs and the Ancient Egyptian language. My attempt was unsuccessful, because of one of the conditions of the Blue Plaque scheme, which (at that time) required, in effect, that the subject should be recognisable to passers-by in the street. It is true that an important function of the plaques is to make a building significant because of its connection with a famous figure, but they also make people aware of significant historical figures who may no longer be widely known. (How many people, for instance, passing 15 Buckingham Gate in SW1 would have heard of Wilfred Scawen Blunt?)

Undeterred by this failure, I tried again, this time on behalf of Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards. A remarkable woman, she is probably best remembered nowadays as the author of that classic work of travel literature, 'A Thousand Miles Up The Nile', but was also a passionate campaigner for the preservation of the remains of Ancient Egypt, and played a key role in the founding of the Egypt Exploration Fund, which became today's Egypt Exploration Society. Before the visit to Egypt which ignited her passion for the Pharaohs, she was also a successful professional journalist, novelist, and editor. (If you want to find out more about her, Brenda Moon's excellent biography 'More Usefully Employed' is available from the EES at the bargain price of £5 in hardback.)

http://www.ees-shop.com/index.php?main_page=index&cPath=2

The mills of God may proverbially grind with exceeding slowness, but I began to think that they had competition in the English Heritage Blue Plaque selection process. I won't weary you with the details, but suffice it to say that the process started in May 2008, and that I finally heard on 3rd March this year that she had not only cleared the selection panel, but that the property owners had agreed the plaque could be mounted on the building, and the plaque itself had actually been created.

At some point in the not too distant future there will be, inshallah, an unveiling ceremony, and a permanent public monument to someone who is sometimes called 'the first woman Egyptologist'.

Egypt in London

The recent Egypt in England seminar at the offices of the Egypt Exploration Society was not only fully booked, but a welcome opportunity to meet friends and colleagues, including a number of subscribers to this newsletter, and to make new contacts. A wide ranging series of talks on the influence of Ancient Egypt on England ranged from the 16th to the 21st century, and gave both speakers and audience plenty to think about. A number of those present were from a background other than traditional Egyptology, and it was noted on more than one occasion that areas like Classical studies had been much more active in developing the study of 'reception', to give it its academic title. Another interesting theme was that of Authenticity, in areas from Architecture and Art through to Advertising, and whether and how much it mattered to the people who were exposed to the Egyptian style.

Feedback has been good, and everyone, organisers, speakers and audience, seemed to enjoy themselves. I, for one, look forward to the next event on this theme, and to this one bearing fruit in the weeks and months to come.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

April

Location, location, location

Important not only to estate agents, but to film directors. The Egypt in Print page on the Egypt in England web site now has a downloadable copy of my recent article for New Empress film magazine on London's Ancient Egyptian film locations. I am very grateful to Helen Cox, Editor in Chief of New Empress, for generously making the article available. Check out the magazine's excellent web site at:

http://newempressmagazine.com/

(The title of the article is an oblique reference to the fact that during his time in London in the 1960's, Arnold Schwarzenegger lived in the same area of London that I do.)

Welcome, Wilkomen, Bienvenue

(To continue the movie references for a moment.) A warm welcome to those who have signed up for this newsletter at one of the talks I have been giving to Ancient Egypt societies around the country. If you haven't already done so, I'd encourage you to browse through the back issues on the web site, and if you have anything to add to them, or any interesting new material on Egypt in England, please do use the email link to let me know.

The Point of Pyramids

In a previous newsletter, I mentioned the mid-eighteenth century Douce mausoleum at Nether Wallop, in Hampshire, and the unusual feature which decorates its summit.

Something about it nagged at the back of my mind, and I was sure that it wasn't simply decorative. It took a bit of digging around, but I finally found what I believe is the source of it in the writings of the fourth century historian Ammianus Marcellinus. In his History, XXII, 15, 29 he says of the Pyramids of Egypt:

"The figure pyramid has that name among geometers because it narrows into a cone after the manner of fire, which in our language is called πῦρ [pyr, as in the root of pyrotechnics]; for their size, as they mount to a vast height, gradually becomes slenderer, and also they cast no shadows at all, in accordance with a principle of mechanics.”

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Ammian/17*.html

Even if his etymology is dubious, this is another indication that such pyramidal mausoleums were not simply copies of the Cestius pyramid in Rome, which many wealthy travellers would have seen during the Grand Tour, but were also references to the writings of classical authors on Egypt. Ammianus had some interesting things to say about obelisks as well, which helps to explain why so many of these in the eighteenth century were decorated with balls and spikes, and I'll come back to that in a future newsletter. And nagging at the back of my mind is another reference, to the bizarre theory of a nineteenth century author that the Pyramids were giant lightning conductors. I know I made notes on it, now all I have to do is find them...

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

May 2014

A Rude Reception

I don't know if it was a Bank Holiday in 1914, but 23rd May was the 100th anniversary of an incident in which suffragettes smashed a mummy case in the British Museum. Without further research I couldn't say which mummy was involved, and if any damage was sustained, but this was one of a spate of attacks around this time on museums and art galleries by suffragettes, often using meat cleavers.

"On 23 May, a glass case holding a mummy was smashed at the British Museum. To avoid further damage, the National Gallery, the Tate Gallery, and the Wallace Collection were all closed until further notice, and the British Museum announced that in future women would only be admitted with a ticket issued on receipt of a letter from a person `willing to be responsible for their behaviour.'" (Andrew Rosen Rise Up, Women! p. 234)

Although the attacks were part of a wider series involving damage to property in general, and in these cases to cultural property, it is a reminder of quite how wide the study of the reception of Ancient Egypt by succeeding cultures can range.

More Usefully Employed

On a more positive note, I hope before long to be able to announce the date of the unveiling of the Blue Plaque to commemorate Amelia Edwards. (See the March 2014 issue of this newsletter.) Staffing changes in the Blue Plaques section have delayed things, but the ceremony should take place later this year.

The Point of Obelisks

In the last issue of this newsletter, I mentioned the writings of the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, also known as Ammian, as the source of the decorative flambeaux on the summit of the Douce pyramidal mausoleum. In his History XVII, 4, 12, he also says that when the obelisk now known as the Lateran obelisk was brought to Rome by Constantius:

“it was finally placed in the middle of the circus [Maximus] and capped by a bronze globe gleaming with gold leaf; this was immediately struck by a bolt of the divine fire and therefore removed and replaced by a bronze figure of a torch, likewise overlaid with gold foil and glowing like a mass of flame.”

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Ammian/17*.html

Constantius had probably been inspired by the example of Augustus, who had set up both the first obelisk in the Circus Maximus, and also that in the Campus Martius (now the Montecitorio obelisk). The latter was set up as the gnomon (shadow caster) of a giant sundial, and capped with a gilt ball on its summit. (Pliny said that this was done in order to concentrate the shadow that it threw.)

These sources, together with the Vatican obelisk, originally capped with a bronze globe believed to hold the ashes of Julius Caesar, and now with a cross and elements from the coat of arms of Sixtus V, explain the enthusiasm in the late Renaissance and Enlightenment for topping obelisks with balls and crosses, which tend to strike us nowadays as inappropriate and un-Egyptian. Once images of surviving obelisks in Egypt itself, in their original state (minus the electrum gilding their pyramidions) became widely available, modern obelisks generally reverted to a more 'correct' form.

Summit of the Vatican obelisk

The original globe from the Vatican obelisk.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

June

Egypt in England Updated

However much research you do, you know that once your book has been published (in pessimistic moments many authors would say as soon as it is published), you will discover new information which you wish could have been included. One advantage of this newsletter is that it offers a way to highlight some of the results of research since Egypt in England was published. This issue features the Case of the Missing Monarch and the Kirkleatham Octohedron.

We are otherwise engaged...

One curious aspect of the story of Cleopatra's Needle was that in spite of huge public interest in its arrival, there was virtually no official presence at its re-erection in London on 12th and 13th September 1878. The Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, had gone behind the hoarding to view the progress of the obelisk from river level and the construction of the pedestal, but was not present when it was finally lowered onto its plinth. As late as 23rd August, The Times had noted that Queen Victoria “was hoped” to attend, but that “to the great regret of Her Majesty” this was “found to be impossible”. The Prince of Wales, who had visited Egypt, had also been expected to attend the ceremonies, but found that he was booked up for some time ahead. Significantly, the British Consul-General to Egypt Hussey Crespigny Vivian, 3rd Baron Vivian, did not attend either, although he was in London “on leave”. He “expressed his regret at having been unable to be present to witness the operation on Thursday”, but was able to visit the site in a private capacity the following day. The reason none of them felt able to attend is suggested by an event that took place less than a fortnight later. On 26th September, Khedive Ismail was deposed by way of a telegram from his sovereign the Ottoman Sultan, having been advised to abdicate a few days earlier but failing to take the hint. However popular the arrival of the Needle in London, at a time of such political tension, seeming to officially celebrate the gift of a ruler considered by many Europeans to have treated Egypt as his private bank account would have been insensitive to say the least. This theory is given added plausibility by passages in Trevor Mostyn's 1989 book 'Egypt's Belle Epoque'. In it, he records that nearly nine years before, when Ismail was welcoming the crowned heads of Europe to the opening of the Suez Canal:

"Queen Victoria allowed the Prince and Princess of Wales to visit Egypt in the February before the inauguration [of the Suez Canal] but, with her full backing, the British Cabinet prevented them from attending the celebrations themselves, only allowing the British Ambassador to the Sublime Porte [Turkish Government] to attend." (p. 104)

Later, on the same page, he notes that the Queen had written to her daughter Vicky, Crown Princess of Prussia, to advise that she and her husband, Prince Frederick, should not attend, as it

"would only make matters worse between the Sultan and Viceroy, or Khedive as he is now called, and they are bad enough."

By the time the Needle arrived in London, they had certainly not improved.

From Cairo to Kirkleatham?

The question of what constitutes Egyptian style architecture can be a tricky one, especially with pre-nineteenth century examples. Take, for instance, the Turner Mausoleum, which is attached to St Cuthbert's Church in Kirkleatham, North Yorkshire.

(Photo courtesy of Simon Armstrong.)

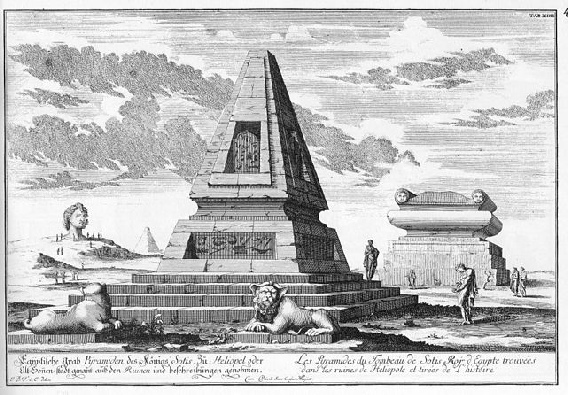

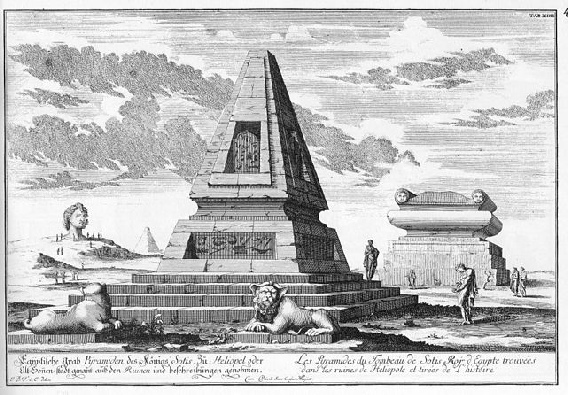

At first the roof may look like a pyramid, but on closer inspection it turns out to have eight sides, to match the octagonal base, and there is nothing Egyptian about the rest of the structure, with its buttresses, bullseye windows and vermiculated rustication. (The bands of textured stonework, but how can you miss the chance to employ a term like 'vermiculated rustication'?) However, when you look into the history of the structure, things start to become interesting. It was designed by the architect James Gibbs, and built in 1739 for Cholmley Turner in memory of his son Marwood, who had died in Lyons while on the Grand Tour. Gibbs had trained in Rome with the architect Carlo Fontana, as had the Austrian architect Johann Fischer von Erlach, who went on to write Entwürff Einer Historischen Architektur (A Plan of Civil and Historical Architecture), one of the earliest comparative studies of world architecture. In his extensively illustrated book, which Gibbs had in his library, von Erlach had included a plate showing what was described in French and German as "The Pyramids of the tomb of Sotis [sic], King of Egypt, found in the ruins of Heliopolis and taken from history". (The site of Heliopolis is now in the north-east suburbs of Cairo.)

True, it has four sides, rather than eight, but Gibbs needed the 'spire' of the mausoleum to accommodate the overall shape of the building. Consider as well his earlier original design for the so-called Boycott Pavilions at Stowe, built around 1728, and subsequently rebuilt with domed roofs. Again eight sided, but basically four sided, with chamfered corners.

Then take a look at the decoration on the top of the Turner mausoleum, described on the Monuments and Mausolea Trust web site (http://www.mmtrust.org.uk/mausolea/view/195/Turner_Mausoleum) as a "flaming urn". (The Boycott pavilion is topped with a ball and spike decoration.) Why put a flaming urn on the top of a pyramid, or at least something that closely resembles it? (Or for that matter a ball and spike.) See the April 2014 Egypt in England newsletter.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb,

Chris

July

What the Douce?

More on the pyramidal Douce mausoleum, which featured in the April newsletter. A number of years ago, it was the subject of an article by Matthew Craske in Church Monuments, the journal of the Church Monuments Society (Church Monuments, Volume XV, 2000, pp. 71-88.), which highlighted some intriguing aspects of its design, and the motivation which led to its construction.

Francis Douce was a member of the Company of Surgeons and the College of Physicians. The pyramidal mausoleum was erected in 1748, but its first occupant was Douce's wife, and he himself was not buried in it until he died in 1760, aged 85. It was designed by John Blake of Winchester, about whom little is known, but who seems to have been doubly unfortunate, having initially underestimated the cost of the work, and then having had to press Douce for payment. He was possibly the anonymous author of two letters in the London Evening Post in November and January of 1748/9 which are important contemporary sources, and include some highly significant details about the pyramid.

Not the least of these is that its unusual position relative to the nearby church results from the fact that the pyramid is aligned to the cardinal points of the compass. This may be intended to to refer to the tradition that the Ancient Egyptians were pioneers of astronomy, and Craske notes that some believed that the summit of the Great Pyramid itself had been used by the Egyptian priests for astronomical observations. The original source for this idea seems to have been the 5th century AD writer Proclus, and it is certainly something that Francis Douce could have known about, as it was mentioned by the mathematician, antiquary and astronomer John Greaves in his Pyramidographia , which he wrote following a visit to Egypt, and which was published in 1646.

Not the least of these is that its unusual position relative to the nearby church results from the fact that the pyramid is aligned to the cardinal points of the compass. This may be intended to to refer to the tradition that the Ancient Egyptians were pioneers of astronomy, and Craske notes that some believed that the summit of the Great Pyramid itself had been used by the Egyptian priests for astronomical observations. The original source for this idea seems to have been the 5th century AD writer Proclus, and it is certainly something that Francis Douce could have known about, as it was mentioned by the mathematician, antiquary and astronomer John Greaves in his Pyramidographia , which he wrote following a visit to Egypt, and which was published in 1646.

However, Greaves noted, very sensibly:

"...that these pyramids were designed as observatories, (whereas by the testimonies of the ancients I have proved before, that they were intended for sepulchres) is no way to be credited upon the single authority of Proclus. Neither can I apprehend to what purpose the priests with so much difficulty should ascend so high, when below with more ease, and as much certainty, they might from their own lodgings hewn in the rocks, upon which the pyramids were erected, make the same observations."

The primary motivation for the construction of Douce's pyramid was not astronomical, though, but funerary, and here a clear connection to Ancient Egypt can be found. We know from the list of subscribers which prefaced it that Douce owned a copy of the Νεκροκηδεία ('Nekrokedieia') of Thomas Greenhill, a fellow member of the Company of Surgeons, published in 1705, which dealt with embalming, and included material on both Egyptian mummies and the Pyramids.

Thomas Greenhill, from the frontispiece of his book, with a step pyramid just visible to the right.

In his will Douce stipulated which undertaker was to prepare his body, with a second alternative named "should he [the first] be dead", and it is likely that he intended his corpse to be embalmed. (Craske provides fascinating information on the role of surgeons as embalmers in this era, and the rising competition they faced from the growing number of undertakers, many of whom came from a background in upholstering or cabinet making, and had questionable skills in the practical aspects of preparing dead bodies.)

Finally, I was delighted to find that in one of the anonymous contemporary letters describing the monument, the author describes estimating the height of the pyramid by its shadow "to the top of the gilt flame". So the decoration on the top was originally gilded, for the probable significance of which see the April and May issues of this newsletter.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

August

England in Egypt

August is traditionally holiday season, and that means books to read on holiday, which suggested to me the idea of a book themed issue of this newsletter. Given the historical popularity of Egypt as a holiday destination for the English, including Florence Nightingale and Amelia Edwards, I thought it would also be nice to turn things on their head, and make it about 'England in Egypt', although the four authors who are featured all lived and worked in Egypt, rather than just visiting it.

James Bond and the Cretan woman

I recently pledged for a copy of 'The Irish Pasha' on Unbound. For those of you that don't already know of it, Unbound is a web site for new books which are published on a subscription model. This was quite extensively used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for books which included Dr Johnson's Dictionary, and Thomas Pettigrew's 'A History of Egyptian Mummies'. Essentially, what happens is that rather than using the traditional model of a writer going to a publisher, who takes on the financial commitment of printing a book, and the risk that it may not recoup its up front advance to the author, let alone sell enough to generate royalties, books are funded by readers, who pledge money, and are only published once they are financially viable. You can find out more on the Unbound web site:

http://unbound.co.uk/

'The Irish Pasha' is a biography of Major Robert Grenville (R G) Gayer-Anderson, known to his friends as 'John'. Nowadays, he is probably best known for the cat. You know, that cat, the one in the British Museum, but he was far more than just the one-time owner of an iconic antiquity.

Gayer-Anderson, although born in Ireland, was educated at Tonbridge School in Kent, and trained as a doctor before being commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and then being seconded to the Egyptian Army, eventually becoming Egyptian Recruiting officer and Oriental Secretary to the High Commissioner and being awarded the elevated rank of Pasha. Both he and his twin brother were enthusiastic and discriminating collectors of Ancient Egyptian antiquities, and much of RG's collection was donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, although the iconic cat was sold to the British Museum in 1947.

Gayer-Anderson, although born in Ireland, was educated at Tonbridge School in Kent, and trained as a doctor before being commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and then being seconded to the Egyptian Army, eventually becoming Egyptian Recruiting officer and Oriental Secretary to the High Commissioner and being awarded the elevated rank of Pasha. Both he and his twin brother were enthusiastic and discriminating collectors of Ancient Egyptian antiquities, and much of RG's collection was donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, although the iconic cat was sold to the British Museum in 1947.

He was also a collector of Islamic antiquities, and his former residence in Cairo, the sixteenth century house, known as 'Beit al-Kretliya' or 'House of the Cretan Woman' is

now a museum. He furnished it with a superb selection of furniture, paintings, carpets and much more, and a library including books on Egyptology and travel to Egypt dating back to the seventeenth and eighteenth century, but despite that it is probably best known as a location for the Bond movie 'The Spy Who Loved Me'.

Beyond the public face of the collector and colonial administrator, however, was a complex personality, a surgeon, a soldier who had survived the carnage of Gallipoli, an artist and poet, and also a homosexual in an era when this was illegal. He was one of those people who seem to attract incident in their lives, as well as one of those who went to rule Egypt, and fell in love with it.

You can find out more about the book at:

http://unbound.co.uk/books/the-irish-pasha

The Mamur Zapt and the Golden Needle

Another Englishman who fell in love with Egypt, and in his case remained there till he died was Joseph McPherson, known by his rank (equivalent to Major) as Bimbashi McPherson. Another veteran of Gallipoli, he became Mamur Zapt, or Head of Secret Police in Cairo, and was involved in combating drugs, gambling and political agitation, as well as mysterious affairs like the death of one Captain King, discovered semi-conscious on a bench in the Ezbekiah Gardens in Cairo, who died in delirium days later after having said nothing but, repeatedly, the phrase "She scratched my eye with a needle and gave me second sight". McPherson's correspondence with his family formed the basis of the excellent book by Barry Carman and John McPherson 'Bimbashi McPherson - A Life In Egypt'.

Russell Pasha and the Father of Bullets

Sir Thomas Russell's English title was trumped by his Egyptian rank of Pasha, equivalent to an English peerage, and he was universally known there as Russell Pasha. He founded the Egyptian Camel Corps, and on his desert patrols rode the thoroughbred Sudanese camel Abu Rusas, 'The Father of Bullets', who as a colt had survived attempted capture by raiding Dervishes, but subsequently bore the souvenir of a hernia from a bullet wound. Russell was also Commandant of the Cairo Police for nearly thirty years, and later ran the Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau. His memoirs, 'Egyptian Service' are packed with incidents, including hashish smuggling on and in camels, and the old woman in Cairo who sold heroin cut with ground human skulls, that read like something from a thriller but are true. They are also full of fascinating detail on things like Egyptian snake charmers and the almost supernatural abilities of the Bisharin trackers used by the Egyptian police.

Quails and the Crossing of the Red Sea

After taking early retirement, Claude Scudamore Jarvis farmed in Hampshire and wrote extensively on natural history, for fourteen years contributing the column 'A Countryman's Notes' to the magazine Country Life, but it is difficult to imagine more of a contrast than the career that had led up to this. Born in the far from rural London suburb of Forest Gate, he had begun his working life in the Merchant Navy, before volunteering for military service in the Second Boer War. Later, after further service in Palestine and Egypt in the First World War, he was seconded to the newly created Egyptian frontiers administration, eventually rising to become Governor of Sinai. As well as his column for Country Life, he wrote a number of other books, including 'Yesterday and Today in Sinai'. Despite its rather dry title, it is another memoir packed with fascinating detail about desert life, travel and wildlife, with vivid incidents of Bedouin blood feuds, drug smuggling and battles against locust swarms. Particularly interesting are his speculations, based on his intimate knowledge of the terrain weather and wildlife of the Sinai, including the migration of quails, on the historical basis of the biblical account of the Exodus and the crossing of the Red Sea.

Apart from 'The Irish Pasha', which has still to be published, all these books are long out of print, but thanks to the wonders of the Internet can all be sourced from your desktop, tablet, or even phone if you choose. Whether you are on holiday or not, they offer a vivid insights into Egypt in another era, its long relationship with England, its effect on the English, and some of the remarkable personalities who were the English in Egypt.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

September

Pavilioned in Splendour

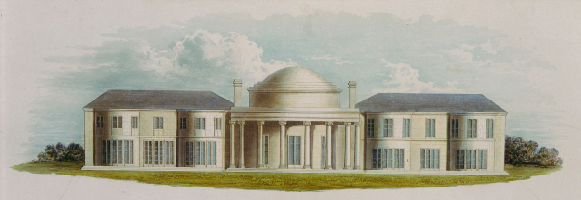

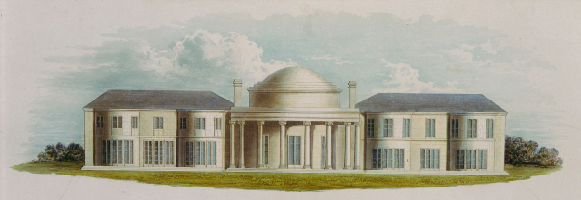

This August, I revisited the Royal Pavilion in Brighton for the first time in many years, and if you haven't been there yet I would urge you to go yourselves. I'd forgotten quite how utterly and wonderfully over the top it is. Originally a farmhouse, it was reconstructed by Henry Holland as a fairly sedate, if substantial, seaside villa for George, Prince of Wales, later George IV, known as the Marine Pavilion.

Then, in 1815, John Nash was commissioned to transform it into the lavish oriental fantasy that it is today, wrapping Holland's structure in a cast iron framework, piling domes and minarets on top of it, and lining its front with columns and latticed screens.

Among those who had unsuccessfully submitted designs for the remodelling of what the tabloids would nowadays probably refer to as the "Prince's Seaside Love Nest" was Humphrey Repton, who considered using the Egyptian style, but rejected it as "too cumbrous for the character of a villa", and Peter Robinson, who worked on its interiors, went on to design the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly. Both of which raise the tantalising question of what an Egyptian Royal Pavilion would have looked like.

In the end, it became an Indian extravaganza inspired by Mughal architecture, but in its transformation it shared much with the Egyptian style buildings of the Regency. Nowadays, we tend to think of this era as one of refined elegance, all sprigged muslin and Jane Austen heroines, but it was also a time of rip roaring commercial expansion, new money and conspicuous consumption. The motto of many seemed to be, in the words of Max Bialystock in 'The Producers', "When you've got it, flaunt it". If you wanted an Egyptian style building, like the Egyptian House in Penzance, or the shop in Fore Street, Hertford, even the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly itself, the easiest way to get it was to slap stucco on an existing structure. The façade was what counted.

Despite its Indian exterior, the dominant theme of the interior was Oriental, particularly Chinese, but other styles were included, particularly of furniture. The Music Room Gallery was at one time decorated in the Egyptian style, and known as the Egyptian Gallery, but sadly (from my point of view, anyway) it was redecorated in the Chinese style in 1815. The current interiors of the Pavilion are not original, as its contents were stripped following its sale to the local authority by Queen Victoria in 1850, when it was thought that the building would be demolished, but many pieces have been returned on loan from other royal palaces, and although others are not original, they are entirely appropriate to the style in which it would have been furnished and decorated. They include a number of pieces reflecting Regency Egyptomania, such as a fairly restrained cabinet in the royal bedrooms upstairs decorated with pharaonic heads, and downstairs a couch with crocodile feet, the Dolphin Suite of furniture, not in itself Egyptian, but with a painted glass shade on a lamp or torchiere commemorating Nelson's victory at the Battle of the Nile, and one of Thomas Hope's clocks in the Egyptian style, with a figure of the goddess Isis. (For an illustration of the latter, see Fig. 156 in Egypt in England.) The magnificent silver gilt dinner service also includes pieces in an Egyptian style.

The fact that its interiors were stripped when it was sold, during the Pavilion's alarmingly close brush with demolition, together with its relatively brief life as a royal palace, and limited subsequent alterations, have paradoxically meant that it could be restored as a coherent whole, and it is one of the best places to appreciate the way in which the Egyptian style took its place in the exuberant eclecticism of Regency taste.

Stony Mountains Built By Art

Photo by Ricardo Liberati

Perhaps only one thing about Egyptian pyramids is certain; that their original builders knew what they were meant to represent and how they were intended to function. Since that knowledge was lost, their antiquity and their very scale itself has ensured speculation on these questions. As regular readers of this newsletter will know, as far back as the Classical era writers from Pliny to Porphyry of Tyre, Ammianus Marcellinus, Decimus Magnus Ausonius and Proclus were writing on them and their origins and function. The tradition that they were the Granaries of Joseph may go back at least as far as the Cosmographia of the 4th century AD writer Julius Honorius. In the 17th century the English astronomer John Greaves concluded from the writings of Herodotus that the Great Pyramid was the tomb of Cheops (Khufu), and rejected the suggestion of Proclus that they had been used as platforms for observing the heavens, but the passage of time brought with it not only scientific investigation of the pyramids, but also increasingly bizarre speculations on their significance. These included the belief that their design was based on a divinely inspired 'Pyramid Inch', and that their dimensions contained records of past history and prophecies of events to come.Of all these manifestations of Pyramidology, however, perhaps the most bizarre was that which I promised to share with you some while ago (April, in fact) in a previous newsletter.

Granaries of Joseph, Basilica of San Marco, Venice ©Chris Elliott

'Revelations of Egyptian Mysteries', or to give it its full title: 'Revelations of Egyptian Mysteries. History of the Creation, the Causes and the Progress of the Degeneration of Nature, the Conflagration and Manner of the Resurrection of the World, as Allegorically Represented by the Egyptian Philosophy: Showing the Justice of the Inculcations of the Egyptian Priests and Wise Men, Teaching that Salt was Fatally Hurtful to Human Nature. With a Discourse of the Maintenance and Acquisition of Health, on Principles in Accordance with the Wisdom of the Ancients.', was written by Robert Howard, and published in London in 1850. Apart from the fact, volunteered by the author himself, that Howard was a 'Practitioner of Medicine', biographical information on Howard is currently scarce to the point of non-existence.

Thanks to the mixed blessing of Google Books, you can if you wish read his work (which today would probably be described as 'life-changing') for yourselves on-line:

Revelations of Egyptian Mysteries

Alternatively, you could rely on my dedication to the cause of scholarship to save you the trouble.

Howard's theories were based on a vision of the Earth as as a living, breathing system, strangely reminiscent of James Lovelock's Gaia Hypothesis, but in Howard's case inspired by a literal understanding of Old Testament scripture. He believed, citing Isaiah Ch. 40 V. 22, that "the land originally formed a continuous circle...extended at a prodigious height above its present surface". Somehow, (quite how is not clear) Man, by interfering with the mineral kingdom, created a layer of stone, "imped[ing] the passage upwards of the subterranean vapours" constantly generated in the interior of the earth, which were no longer "absorbed and solidified" but trapped, giving rise to explosive mixtures and subterranean lightning. These became the cause of earthquakes and cataclysmic explosions which formed the present continents. We are, as he put it "the inhabitants of the wreck of the former world".

He notes that earthquakes are linked to volcanic countries, but are "almost unknown" in "old worn-out desert regions" such as Upper Egypt, "as is also the case with thunder and lightning". Noting the fertility of volcanic soils, he saw volcanoes as Nature's way of restoring the earth's fertility. However, inspired by texts including Psalm 83 V. 14 "as the flame setteth the mountains on fire", he believed that stone was actually "ignited by volcanic fire", and he attributed the violence of submarine eruptions, or those where lava flows into the sea, to "explosive burning of the waters", arguing that "as the smith's fire will not burn with sufficient intensity without constant wetting, so will not the volcanic process go on with vigour without a constant supply of water". Noting that torrential rain and lightnings were associated with volcanic eruptions, he saw these as Nature's way of supplying this water.

Photo by Oliver Spalt

How, you may be asking by now, does this relate to the "stony mountains built by art, commonly called pyramids", not "sepulchral monuments", but "certainly intended to serve some other great and unknown purpose"? Well, volcanic eruptions produce torrents of rain and lightning that spread far from the initial eruption. The lightning, according to Howard, ignites the stone of mountain peaks, uncovered by earth, the simultaneous downpour of rain feeds the fire " the fury of the fire being prodigiously increased", and the very stone melts and runs like water over the surrounding countryside, subsequently renewing its fertility. Sharp peaked mountains, according to Howard, are "the matches which nature erects to receive the celestial fire, in order that the earth may become kindled". No mountains? Then build pyramids ready for the "next terrestrial conflagration". Just as high structures attract lightning today, their summits would attract the celestial fire. If you are wondering where the necessary water to sustain the conflagration would come from in the deserts of Egypt, the answer is that "those pyramids which have been entered are found to contain vast cisterns and reservoirs for water", and their sloping shape was to aid the collection of rain to feed these.

So there you have it. The real reason behind the building of the pyramids. It's unlikely that you are ever likely to find yourselves at Giza with a thunderstorm looming, but if you do you might want to start heading back to Cairo, without making too much of a fuss about it. You'd only have to explain why.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

October 2014

Happy Silver Anniversary

To Leicester Ancient Egypt Society, who were kind enough to invite me to speak to their members last month on the occasion of their 25th anniversary, and a warm welcome to those who signed up for this newsletter then. Of the Egypt societies around the country that I have visited, I'm not sure which is the oldest (feel free to stake your claims), but the anniversary got me thinking about the role that such societies have played in promoting interest in Ancient Egypt, and helping to spread its influence.

"Any gentleman who has been in Egypt..."

The first society in England devoted to Ancient Egypt must have been the original Egyptian Society, founded in December 1741 after a dinner at the Lebeck's Head Tavern in London's Chandos Place. Modelled on the earlier Society of Dilettanti, which brought together gentlemen who had visited Italy on the Grand Tour, and allowed them to discuss Classical culture and antiquities, its founding members included not only John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, who presided, but Richard Pococke, Charles Perry and Frederic Norden, all of whom had visited Egypt and written books about it on their return.

Other members included William Lethieullier, who donated one of the first Egyptian mummies in the British Museum's collections, and the antiquarian Rev. William Stukeley, now best remembered for his eccentric theories on the Druids, who lectured to the Society on the origins of the sistrum, the hooped rattle associated with the goddess Hathor, one of which (quite possibly genuine Egyptian) was used by the President to call for silence at the meetings. Existing members could propose new members, "gentlemen who had been in Egypt", who were elected by majority vote. Those who had not visited Egypt could also join, but their numbers were restricted to thirty, although it seems that the Society's total membership never exceeded twenty-five.

Officers of the Society had modern Egyptian titles, the President being styled 'Sheik', the Secretary 'Reis Effendi', and the Treasurer 'Hasnader' or 'Haznadar'. Many of the members were Freemasons, and at this time Masonic lodges also customarily met in taverns. A number of members were also Fellows of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries, even serving as their Presidents. Despite this, there are grounds for believing that meetings were not wholly devoted to academic and intellectual topics. The picture opposite, of which the original is in the Getty Museum, is a portrait from 1744 of Sir Bouchier Wray, a member of the Society of Dilettanti, and shows him serving punch aboard a ship at sea. The text around the rim of the bowl is a quote from the Odes of Horace - “Dulce est Desipere in Loco” (It is sweet at fitting time to act foolishly), and early members of the Dilettanti were criticised in 1743 by Horace Walpole for their relaxed attitude towards sobriety. The minute book of the Egyptian Society, which has survived, has a reference to the Treasurer having to "answer the draughts of the Reis Effendi and give an account to the Society of his receipts".

Officers of the Society had modern Egyptian titles, the President being styled 'Sheik', the Secretary 'Reis Effendi', and the Treasurer 'Hasnader' or 'Haznadar'. Many of the members were Freemasons, and at this time Masonic lodges also customarily met in taverns. A number of members were also Fellows of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries, even serving as their Presidents. Despite this, there are grounds for believing that meetings were not wholly devoted to academic and intellectual topics. The picture opposite, of which the original is in the Getty Museum, is a portrait from 1744 of Sir Bouchier Wray, a member of the Society of Dilettanti, and shows him serving punch aboard a ship at sea. The text around the rim of the bowl is a quote from the Odes of Horace - “Dulce est Desipere in Loco” (It is sweet at fitting time to act foolishly), and early members of the Dilettanti were criticised in 1743 by Horace Walpole for their relaxed attitude towards sobriety. The minute book of the Egyptian Society, which has survived, has a reference to the Treasurer having to "answer the draughts of the Reis Effendi and give an account to the Society of his receipts".

After a brief life, the Egyptian Society was dissolved in 1743, for reasons which are unclear, but it had helped to spread the experiences of travellers to Egypt at a time when the country was still difficult to access and hazardous to travel in, and however much it emulated the approach of the Dilettanti, whose motto was 'Seria Ludo', or the serious dealt with light-heartedly, it included key figures in the transmission of information about Ancient Egypt in the eighteenth century.

It was not until the nineteenth century that the next Egyptian Society appeared, this time founded around 1817 by Thomas Young to coordinate the publication of all existing copies of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Young, whose rivalry with Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs is part of Egyptological history, failed to achieve his immensely ambitious goal, but again the formation of a society was one indication that the study of Ancient Egypt was moving onto a more systematic basis.

It was not until the nineteenth century that the next Egyptian Society appeared, this time founded around 1817 by Thomas Young to coordinate the publication of all existing copies of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Young, whose rivalry with Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs is part of Egyptological history, failed to achieve his immensely ambitious goal, but again the formation of a society was one indication that the study of Ancient Egypt was moving onto a more systematic basis.

As the nineteenth century progressed, local literary and scientific bodies began to spring up round the country, particularly in London. One of these was the Tooting Literary Society, where in 1832 the journalist and amateur Egyptologist Edward Clarkson gave a series of three lectures on Egyptian Antiquities to what the Gentleman's Magazine for March of that year described as "the neighbouring gentry from Clapham, Streatham and Croydon". His lectures were on The Pyramids; Temples, Palaces and Tombs; and The Hieroglyphical Language. Topics that are still being lectured on today, but Clarkson's take on them was somewhat different.

According to him, the pyramids were not tombs, but "cavern oracles" in which were practised the primitive religion of mankind, before "the dynasty of the Thutmosis and the Amenophs introduced civilisation, division of lands, and idolatry together". His second lecture, showing that alternative chronologies are nothing new, put forward the view that there had been no civilisation before the first Thutmosis, and that a group of the 'Sea Peoples' whose defeat by Ramesses III is shown in reliefs on the temple of Medinet Habu became the Toltecs who built the pyramids of South America. As a finale, his third and final lecture divided hieroglyphs into three types; Anaglyphical, Phonetic, and Ideographical. What precisely he meant by these terms it is difficult to be sure, but at another lecture not long afterwards at an unnamed venue in Highgate, he "emphatically declared that he was at total variance with Champollion's recent hypothesis", maintaining that hieroglyphs were "purely ideographical", and declaring that the "mathematical logic of the deciphering art" had furnished a key to their true meaning. He then read "part of the hieroglyphical inscription on the Rosetta Stone, pointing out the mathematical certainty on which the interpretation rested". It would be interesting to know what he believed that interpretation to be.

After that, it is a positive relief to be able to turn to the Islington Literary and Scientific Institution, whose lecture on 9th January 1839 was 'Mr Pettigrew on Mummies' (followed the week after by 'The President, on Blowpipes'). Thomas 'Mummy' Pettigrew was the premier mummy unroller of the nineteenth century, as well as the author of the first comprehensive modern study of them, and four days after his talk, in the theatre of the Institution, before an audience of 350 members and their friends, who had each paid half a crown (two shillings and sixpence) for tickets, he unrolled a mummy from Thebes, identified as that of "Ohranis, daughter of the Priest of Mandoo, Bal Snauf". Although the names would nowadays be read very differently ('Mandoo' is probably the Theban god Montu) his translation of the inscriptions on the mummy case was broadly correct, and allowed him to deduce that priestly offices were hereditary among the Ancient Egyptians. For his trouble, Pettigrew was paid the sum of five guineas (five pounds five shillings), which allowing for inflation would correspond to a modern lecturer's fee of over £300, and probably a share of the ticket money from the unrolling.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the study of Ancient Egypt increasingly became the preserve of learned societies such as the Syro-Egyptian Society and later the Society of Biblical Archaeology, but the growth of modern tourism, and the rise of Egypt as a destination, meant that there were still audiences eager to learn more about Ancient Egypt on their return, and for those who could not afford to visit the Land of the Pharaohs, there were the panoramas, the Victorian precursors of cinema. In 1849 the two worlds overlapped when members of the Syro-Egyptian Society were invited by the proprietors to an exclusive showing of the Nile Panorama, where the artist and Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi, who had been instrumental in its creation, lectured to an audience of over two hundred people. (Nile Panorama logo from Bonomi correspondence, courtesy of Yvonne Neville-Rolf.)

As the nineteenth century progressed, the study of Ancient Egypt increasingly became the preserve of learned societies such as the Syro-Egyptian Society and later the Society of Biblical Archaeology, but the growth of modern tourism, and the rise of Egypt as a destination, meant that there were still audiences eager to learn more about Ancient Egypt on their return, and for those who could not afford to visit the Land of the Pharaohs, there were the panoramas, the Victorian precursors of cinema. In 1849 the two worlds overlapped when members of the Syro-Egyptian Society were invited by the proprietors to an exclusive showing of the Nile Panorama, where the artist and Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi, who had been instrumental in its creation, lectured to an audience of over two hundred people. (Nile Panorama logo from Bonomi correspondence, courtesy of Yvonne Neville-Rolf.)

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

November 2014

Remember, remember...

This month marks the ninety-second anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, and I had fully intended to devote this issue of the newsletter to that hardy perennial, the Curse of King Tut. After all, however heavily Egyptologists may sigh when it comes up yet again, in the popular imagination Ancient Egypt means mummies, and mummies (especially royal ones) mean curses. Then, while using the Internet for research, I came across something that I simply couldn't resist. Curse, schmurse. This issue became about the mummy as meme.

In a proposal to a publisher, I once observed that if you projected an image of the gold mask of Tutankhamun on the moon, the majority of the world's population would probably recognise it, even if they might have trouble identifying it. The term 'iconic' is becoming ever more clichéd, but if any image qualifies, it must be the face of the boy pharaoh. His image, or to be more precise the image of his mask, has taken on a life of its own. No longer just representing him, or even the object itself, it has become a sort of shorthand for Ancient Egypt and everything associated with it. More than that, as it has been used in other contexts, it has undergone all sorts of changes, while still remaining recognisable. (Try searching "King Tut products" on Google Images.) It has become a meme.

In a proposal to a publisher, I once observed that if you projected an image of the gold mask of Tutankhamun on the moon, the majority of the world's population would probably recognise it, even if they might have trouble identifying it. The term 'iconic' is becoming ever more clichéd, but if any image qualifies, it must be the face of the boy pharaoh. His image, or to be more precise the image of his mask, has taken on a life of its own. No longer just representing him, or even the object itself, it has become a sort of shorthand for Ancient Egypt and everything associated with it. More than that, as it has been used in other contexts, it has undergone all sorts of changes, while still remaining recognisable. (Try searching "King Tut products" on Google Images.) It has become a meme.

The term "meme" originated in the 1970s, and was derived from the Greek 'mimema', "that which is imitated". (The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawson is often given credit for it.) Its precise meaning is tricky to define, but the Oxford English Dictionary considers it to be an element of a culture which is passed between individuals by imitation. Other dictionaries have the sense of an idea, behaviour or style, or unit of cultural information, which spreads between individuals. The term was coined by analogy with 'gene', and suggests that in a way similar to that in which specific traits such as hair and eye colour can be coded in particular genes, elements of culture can be transmitted almost independently of the context in which they originate. One of the most common uses for the term is to describe the images, often intended to be humorous, that are copied and spread, with slight variations, over the Internet. You could argue that transmission by posting on the Internet isn't between individuals, but two crucial elements of a meme are that it can be copied, and also modified or evolved. Memes emerge as individuals share pre-existing cultural symbols, including elements of Ancient Egypt.

Now, you might argue that genes have an actual physical existence, whereas, (here someone, somewhere, is adding 'so-called') memes do not. A fair point, but then neither do ideas, and yet we routinely use the concept. When I was researching and writing Egypt in England, one of the key issues I had to decide for myself was what qualified as 'Egyptian style' architecture, and for me it boiled down to the use in a single building of enough specific and identifiable elements such as winged solar disks, torus mouldings, battering, and cavetto cornices. Still recognisably Egyptian, and still discrete elements, but a long way from their original context. Copied by architects from originals, reference sources, or each others' work, they were behaving like memes, being incorporated into buildings whose overall forms and functions were seldom anything to do with the original context of these elements, but giving them an 'Egyptian' identity. If the process went too far, as for example when Egyptian elements were incorporated into the Art Deco style, they were 'digested', and evolved into forms whose originals were no longer recognisable. Sometimes, however, memes can change without losing their original identity, and the image I referred to at the beginning of this newsletter was a wonderful example of this.

What I had come across was a hybrid. The golden mask of Tutankhamun crossed with the Guy Fawkes mask of the anarchist revolutionary from the graphic novel and film 'V for Vendetta'. The meme of the Guy Fawkes mask was taken up by the internet focussed activist group Anonymous, and the masks have been worn by protesters in Egypt. The image on the left, taken on November 29th 2011 was posted by Gigi Ibrahim on Flickr with the caption, "Egyptian Anonymous". (If you look carefully you can also see the 'A in a circle' anarchist symbol among the Arabic writing.) What fascinated me was that it combined two clearly distinct memes, each of which remained identifiable. The Guy Fawkes mask an image associated with an important date in English history, now a symbol of both anonymity and revolution, the mask of Tutankhamun a quintessential symbol of Egypt, even in the modern Islamic state.

What I had come across was a hybrid. The golden mask of Tutankhamun crossed with the Guy Fawkes mask of the anarchist revolutionary from the graphic novel and film 'V for Vendetta'. The meme of the Guy Fawkes mask was taken up by the internet focussed activist group Anonymous, and the masks have been worn by protesters in Egypt. The image on the left, taken on November 29th 2011 was posted by Gigi Ibrahim on Flickr with the caption, "Egyptian Anonymous". (If you look carefully you can also see the 'A in a circle' anarchist symbol among the Arabic writing.) What fascinated me was that it combined two clearly distinct memes, each of which remained identifiable. The Guy Fawkes mask an image associated with an important date in English history, now a symbol of both anonymity and revolution, the mask of Tutankhamun a quintessential symbol of Egypt, even in the modern Islamic state.

To me, one of the most fascinating aspects of Ancient Egypt is how its culture has survived, and influenced succeeding cultures over the centuries. It has not survived intact and unchanged, however. Elements of it have become 'detached', and often acquired additional or alternative meanings, while still being associated with Egypt. The Egyptian Anonymous image, stencilled on a wall in Egypt, shows that process is still happening. Here, one of the most iconic images in the world has been combined with one of the most iconic in English history, and in an especially appropriate coincidence, the day before the English Egyptologist Howard Carter sent his famous telegram to Lord Carnarvon, the day on which his excavations revealed twelve steps leading down to a sealed entrance, was November 5th - Bonfire Night.

The Curse of King Tut?

Having whetted your appetites for the uncanny at the beginning of this newsletter, I suppose that it would be unfair of me to finish without saying anything about the Curse of King Tut. As another possible example of its awesome (if apparently rather erratic and unpredictable) effects, you may like to consider the following. In late December 1942, the British T Class submarine P311 was lost on operations in the Mediterranean before her name had been formally allocated. If it had been, she would have been called... H M S Tutankhamun.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

December

Deck the Halls...

It's true, as I pointed out in the December newsletter last year, that there's nothing very Ancient Egyptian about Christmas, but Abydos, which had always been important in Pharaonic Egypt, continued to be a site of pilgrimage into Graeco-Roman times. The Mortuary Temple of Sety I, known during the latter era as the Memnonium, was associated with Sarapis rather than Osiris, but a popular time to visit was in the month of Choiak, when a festival of Osiris was still held. In our calendar, Choiak ran (or still runs, if you care to observe it) between November 27th and December 26th. That's close enough to Christmas.

'Tis the Season...

In 1892, in his book 'Cairo, Sketches of its History, Monuments and Social Life', Stanley Lane-Poole observed that "a visit to Egypt is now an ordinary Christmas holiday", but that was more a case of England in Egypt than Egypt in England. However, if you had sampled the delights of the Royalty Theatre, near the Tower of London, at Christmas in 1803, you would have been able to see the pioneer Egyptologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni in his earlier incarnation as 'The Patagonian Sampson'. More than half a century later, a play by one Roger Williams entitled 'Egypt 3,000 years ago, or Queen Cleopatra: a dream in the Crystal Palace' was performed during December 1854 and January 1855 at The Britannia in the High Street in Shoreditch. (A now achingly trendy district of North London, for those of you unfamiliar with it.) Given its intriguing title, there is disappointingly little information on it. Two playbills survive, which indicate that it was one of a number of short, possibly one act, plays (with titles such as 'Fashion and Famine!' and 'The Aztec Children') and other performances, including a singer, that formed an evening's entertainment. From the fact that some titles change between playbills, we can deduce that 'Egypt 3,000 years ago...' was the main feature, and the others were supporting material. The reconstructed Crystal Palace, with its Egyptian Court, had opened in June 1854, and the play would probably have been a popular topical item for the traditional Christmas and Pantomime season.

Christmas, all wrapped up...

It's coming up to Christmas, you've got a few friends coming round, so what do you do to entertain them? In late December 1848, in the case of the architect Decimus Burton (one of the subscribers to Thomas Pettigrew's 'A History of Egyptian Mummies'), you raffle a mummy. In this case one belonging to George Greenough, which had been given to him a number of years before by Burton's elder brother, the traveller to Egypt James Burton. Greenough had loaned James money, and the mummy probably represented a partial repayment in kind. With only four people in the raffle, chances of a winning ticket were high, and the lucky man was Edmund Hopkinson, a partner in Hopkinson's Bank, and Decimus' brother-in-law. Hopkinson took the mummy back to Gloucester, where it was unrolled by a local doctor, and then given to the newly-formed Gloucester Museum. Eventually, it was transferred in 1953 to Liverpool Museum to replace a mummy casualty of wartime bombing. (See Neil Cooke's 'The Forgotten Egyptologist' pp. 85-94 in Paul and Janet Starkey's 'Travellers in Egypt'.)

It may not be significant, but when preparing this issue of the newsletter it struck me that a number of mummy unrollings took place in December. One of these, as well as one of the last mummy unrollings before non-destructive examination techniques (first X-rays and later CAT scans) became the norm, was that of the 21st or 22nd Dynasty mummy of Bak-Ran. It was unrolled at University College London on either 15th or 18th December 1889 (sources differ) by Wallis Budge. In the audience were the writer of 'Cleopatra', Rider Haggard, and the painters Laurence Alma-Tadema and E J Poynter, both of whom produced works depicting Ancient Egypt.

Poynter was married to one of Rudyard Kipling's aunts, and another aunt was married to the painter Edward Burne-Jones. As a child, Kipling spent each December with the Burne-Joneses at their house in Fulham, and it was on one of these visits, as he recounts in his autobiography 'Something of Myself', that his uncle

"...descended in broad daylight with a tube of 'Mummy Brown' in his hand, saying that he had discovered it was made of dead Pharaohs and we must bury it accordingly. So we all went out and helped - according to the rites of Mizraim and Memphis, I hope -and- to this day I could drive a spade within a foot of where that tube lies."

I have come across this anecdote in other contexts, where it is obvious that the writer has taken it in all seriousness, but for me it conjures up a wonderful vision of Kipling and sundry other small children trooping into the garden with his uncle and playing along with his pretended horror at his unwitting sacrilege.

Compliments of the Season

What, I thought to myself, could be better to curl up with at Christmas than a mummy story? (That is a rhetorical question, by the way, please don't email me with your alternatives.) And so, courtesy of the University of Adelaide, a small Christmas gift from Egypt in England.

A Professor of Egyptology - Guy Boothby

One hundred and twenty years ago, it was enjoyed by readers of The Graphic in that publication's December issue. But please, do remember, a mummy is for afterlife, not just for Christmas.

And Finally...

Included with this issue of the newsletter is your Christmas Card from myself and Neferwety.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

Not the least of these is that its unusual position relative to the nearby church results from the fact that the pyramid is aligned to the cardinal points of the compass. This may be intended to to refer to the tradition that the Ancient Egyptians were pioneers of astronomy, and Craske notes that some believed that the summit of the Great Pyramid itself had been used by the Egyptian priests for astronomical observations. The original source for this idea seems to have been the 5th century AD writer Proclus, and it is certainly something that Francis Douce could have known about, as it was mentioned by the mathematician, antiquary and astronomer John Greaves in his Pyramidographia , which he wrote following a visit to Egypt, and which was published in 1646.

Not the least of these is that its unusual position relative to the nearby church results from the fact that the pyramid is aligned to the cardinal points of the compass. This may be intended to to refer to the tradition that the Ancient Egyptians were pioneers of astronomy, and Craske notes that some believed that the summit of the Great Pyramid itself had been used by the Egyptian priests for astronomical observations. The original source for this idea seems to have been the 5th century AD writer Proclus, and it is certainly something that Francis Douce could have known about, as it was mentioned by the mathematician, antiquary and astronomer John Greaves in his Pyramidographia , which he wrote following a visit to Egypt, and which was published in 1646.

Gayer-

Gayer-

Officers of the Society had modern Egyptian titles, the President being styled 'Sheik', the Secretary 'Reis Effendi', and the Treasurer 'Hasnader' or 'Haznadar'. Many of the members were Freemasons, and at this time Masonic lodges also customarily met in taverns. A number of members were also Fellows of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries, even serving as their Presidents. Despite this, there are grounds for believing that meetings were not wholly devoted to academic and intellectual topics. The picture opposite, of which the original is in the Getty Museum, is a portrait from 1744 of Sir Bouchier Wray, a member of the Society of Dilettanti, and shows him serving punch aboard a ship at sea. The text around the rim of the bowl is a quote from the Odes of Horace -

Officers of the Society had modern Egyptian titles, the President being styled 'Sheik', the Secretary 'Reis Effendi', and the Treasurer 'Hasnader' or 'Haznadar'. Many of the members were Freemasons, and at this time Masonic lodges also customarily met in taverns. A number of members were also Fellows of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries, even serving as their Presidents. Despite this, there are grounds for believing that meetings were not wholly devoted to academic and intellectual topics. The picture opposite, of which the original is in the Getty Museum, is a portrait from 1744 of Sir Bouchier Wray, a member of the Society of Dilettanti, and shows him serving punch aboard a ship at sea. The text around the rim of the bowl is a quote from the Odes of Horace - It was not until the nineteenth century that the next Egyptian Society appeared, this time founded around 1817 by Thomas Young to coordinate the publication of all existing copies of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Young, whose rivalry with Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs is part of Egyptological history, failed to achieve his immensely ambitious goal, but again the formation of a society was one indication that the study of Ancient Egypt was moving onto a more systematic basis.

It was not until the nineteenth century that the next Egyptian Society appeared, this time founded around 1817 by Thomas Young to coordinate the publication of all existing copies of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Young, whose rivalry with Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs is part of Egyptological history, failed to achieve his immensely ambitious goal, but again the formation of a society was one indication that the study of Ancient Egypt was moving onto a more systematic basis. As the nineteenth century progressed, the study of Ancient Egypt increasingly became the preserve of learned societies such as the Syro-

As the nineteenth century progressed, the study of Ancient Egypt increasingly became the preserve of learned societies such as the Syro- In a proposal to a publisher, I once observed that if you projected an image of the gold mask of Tutankhamun on the moon, the majority of the world's population would probably recognise it, even if they might have trouble identifying it. The term 'iconic' is becoming ever more clichéd, but if any image qualifies, it must be the face of the boy pharaoh. His image, or to be more precise the image of his mask, has taken on a life of its own. No longer just representing him, or even the object itself, it has become a sort of shorthand for Ancient Egypt and everything associated with it. More than that, as it has been used in other contexts, it has undergone all sorts of changes, while still remaining recognisable. (Try searching "King Tut products" on Google Images.) It has become a meme.

In a proposal to a publisher, I once observed that if you projected an image of the gold mask of Tutankhamun on the moon, the majority of the world's population would probably recognise it, even if they might have trouble identifying it. The term 'iconic' is becoming ever more clichéd, but if any image qualifies, it must be the face of the boy pharaoh. His image, or to be more precise the image of his mask, has taken on a life of its own. No longer just representing him, or even the object itself, it has become a sort of shorthand for Ancient Egypt and everything associated with it. More than that, as it has been used in other contexts, it has undergone all sorts of changes, while still remaining recognisable. (Try searching "King Tut products" on Google Images.) It has become a meme. What I had come across was a hybrid. The golden mask of Tutankhamun crossed with the Guy Fawkes mask of the anarchist revolutionary from the graphic novel and film 'V for Vendetta'. The meme of the Guy Fawkes mask was taken up by the internet focussed activist group Anonymous, and the masks have been worn by protesters in Egypt. The image on the left, taken on November 29th 2011 was posted by Gigi Ibrahim on Flickr with the caption, "Egyptian Anonymous". (If you look carefully you can also see the 'A in a circle' anarchist symbol among the Arabic writing.) What fascinated me was that it combined two clearly distinct memes, each of which remained identifiable. The Guy Fawkes mask an image associated with an important date in English history, now a symbol of both anonymity and revolution, the mask of Tutankhamun a quintessential symbol of Egypt, even in the modern Islamic state.

What I had come across was a hybrid. The golden mask of Tutankhamun crossed with the Guy Fawkes mask of the anarchist revolutionary from the graphic novel and film 'V for Vendetta'. The meme of the Guy Fawkes mask was taken up by the internet focussed activist group Anonymous, and the masks have been worn by protesters in Egypt. The image on the left, taken on November 29th 2011 was posted by Gigi Ibrahim on Flickr with the caption, "Egyptian Anonymous". (If you look carefully you can also see the 'A in a circle' anarchist symbol among the Arabic writing.) What fascinated me was that it combined two clearly distinct memes, each of which remained identifiable. The Guy Fawkes mask an image associated with an important date in English history, now a symbol of both anonymity and revolution, the mask of Tutankhamun a quintessential symbol of Egypt, even in the modern Islamic state.